“Joy Silk” Would Mean More NLRB Elections, Not Fewer

Accusations that the doctrine serves as a stealthy stand-in for card check completely miss the mark.

The opposition to NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo’s inclusion of the Joy Silk doctrine in her GC Memo has so far been relatively muted. Despite its potential re-introduction into case law representing one of the “most dramatic changes to labor law in the last 40 years” (according to labor law professor Matthew Bodie), management-side criticism of the Memo has mostly been limited to warnings regarding changes to Trump-era case law such as handbooks, e-mail, arbitration agreements, and property rights. Few seem to grasp the significance of the difference between Joy Silk bargaining orders and the frail framework existing under Gissel.

But yesterday I came across a management-side client update that appears to grasp the seriousness of the matter. As one BakerHostetler attorney puts it:

Perhaps most alarming, the memorandum requires regional staff to seek guidance in cases where an employer declines to recognize a union based on a showing of authorization cards without offering an explanation for doubting the union’s claim of majority status. In short, the inclusion of this reference in the memorandum suggests that the new general counsel is looking for ways to impose a form of card check recognition without the need for congressional action.

This attorney is right to emphasize the potential impact of Joy Silk on the status quo of modern union recognition requests. But it is wrong and misleading to suggest that the point of the doctrine is to covertly implement a card-check system under the National Labor Relations Act. Putting the merits of card check aside, this reveals a lack of understanding of both the Joy Silk doctrine as it operated in its time and the history of NLRB elections since the doctrine’s departure from case law in 1969.

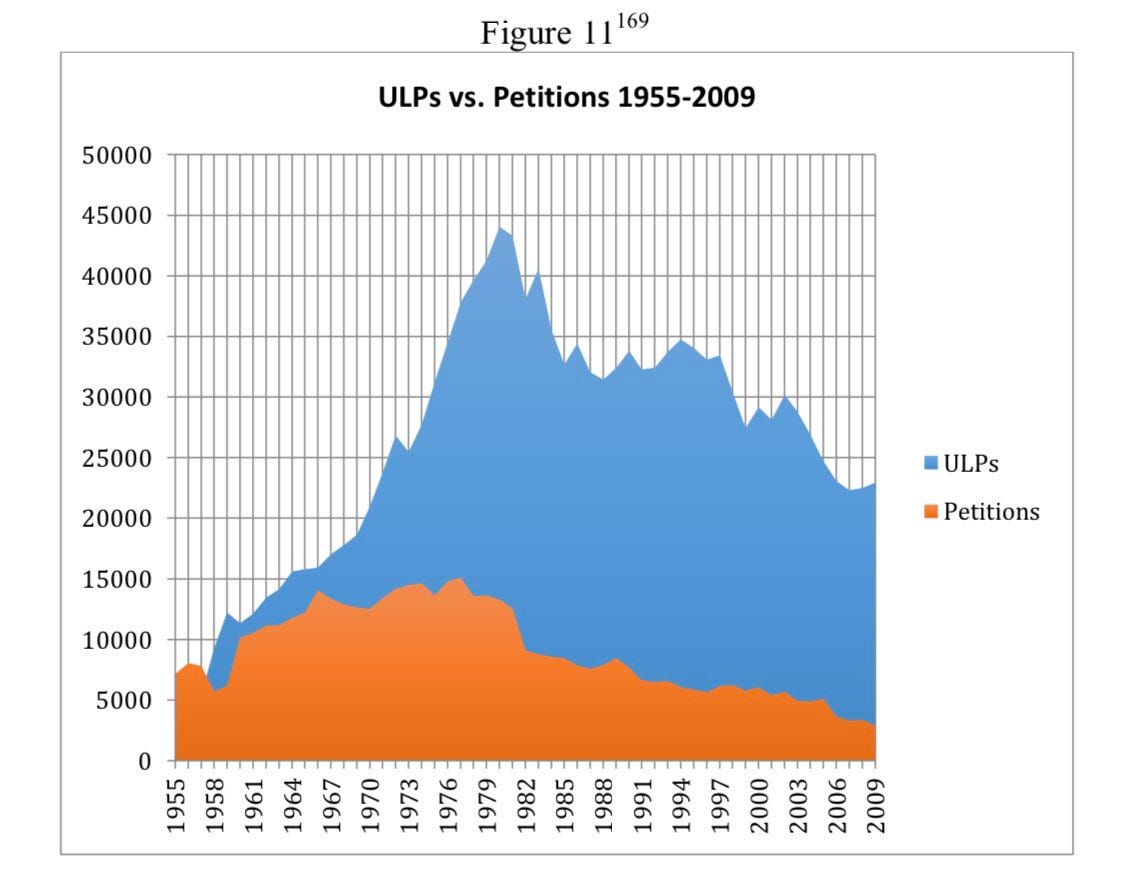

First, as I have explained, the NLRB never treated Joy Silk bargaining orders as the equivalent of card check either substantively or numerically. While Joy Silk cases ate an increasing share of the agency’s unfair labor practice docket, they still constituted a tiny portion compared to its representation function:

The Kennedy-Johnson Board’s re-embrace of Joy Silk bargaining orders led to a marked increase in organizing through authorization cards. The number of bargaining orders issued by the Labor Board based on card majorities rose from 35 in 1963 to 157 by 1967. This, however, remained a small portion of the Board’s work; unions awarded recognition by cards rather than secret-ballot elections rose from a share of 1.1 percent in 1962 to 3.6 percent in 1968. Over 8,000 elections were held in 1967 alone.

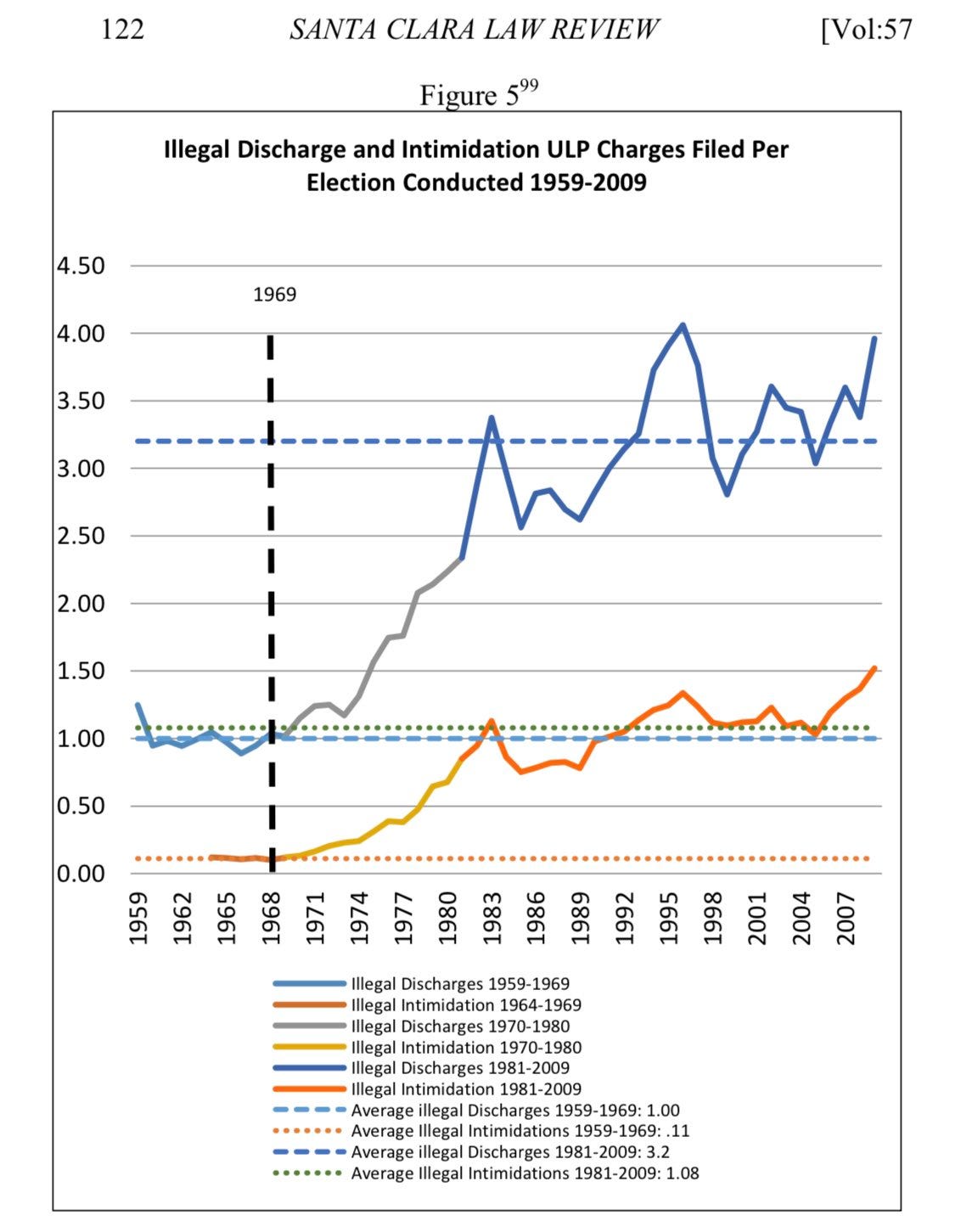

If Joy Silk was really just a duplicitous means of achieving card check, then why did the vast majority of unions in the 1960s proceed to an election? The answer is that even if a union undertook an organizing strategy based explicitly upon means of tripping up an employer to prove a lack of good faith doubt, the NLRB almost never issued a bargaining order without the presence of separate unfair labor practices. (An exception was the Snow & Sons case, where an employer reneged on an agreed-upon card check with the union and demanded an election without previously expressing doubt about the validity of the authorization cards.) Logistically, then, there wasn’t as much opportunity for bargaining orders in the 1960s, when employers committed unfair labor practices at a fraction of the rate they do today:

This explanation bleeds into my second point. NLRB elections have rapidly diminished in number over the last several decades, barely hovering above 1,000 total in recent years (compared to over 8,000 in 1970). As Brian Petruska has demonstrated in his excellent article on the doctrine, Joy Silk was the hull that kept this ship afloat:

Critics say that the purpose of restoring Joy Silk is to reduce the number of Board-supervised representational elections. This criticism seriously misjudges the likely effects of Joy Silk. Rather than reduce elections, the Joy Silk doctrine’s most likely and immediate effect will be to seriously reduce the incidence of ULPs. Under Joy Silk, an employer who wishes to resist unionization faces two options: 1) to commit ULPs and bring upon itself years of litigation that ultimately lead to a bargaining order, and, after that, months of tough bargaining to avoid an agreement; or 2) engage in a lawful campaign of persuasion with employees prior to an election, and, if that is unsuccessful, months of tough bargaining to avoid an agreement. Between these two options, the first option is far more costly and has the added drawback of leading to the same destination as the less costly second option. Rational employers will see this logic and follow the latter option—that is, they will insist upon elections and avoid ULPs. This choice will result in elections occurring at higher rates, but with far fewer ULPs.

Indeed, those who would suggest that Joy Silk will reduce the number of secret ballot elections have it exactly backwards: It was the abandonment of Joy Silk and the adoption of Gissel that has massively reduced secret-ballot collective bargaining elections in this country. … The Board’s experience with Joy Silk, therefore, shows that Joy Silk had no effect of limiting elections. To the contrary, Joy Silk is necessary to provide a sufficient level of protection to make more numerous elections feasible.

Petruska’s commonsense argument—that elections are less likely to be held in an environment in which employers’ unfair labor practices run rampant with little consequences—is backed by unassailable data. The conclusion is inescapable: as bargaining orders all but disappeared from the NLRB’s arsenal of remedies under the higher threshold of the Gissel standard (which generally require evidence of “outrageous” and “pervasive” ULPs for courts to even entertain them), employers systematically increased their use of unlawful activity to clamp down on union organizing. As elections became more difficult for unions to win, unions began to abandon the NLRB certification process en masse and pursue other means of organizing, if they decided to keep organizing at all. The result is a hollowed-out election machinery under which only the most bulletproof campaigns can win and the most incompetent employers can lose. As Petruska argues, the current scenario of few elections and plentiful ULPs “constitutes a profound perversion of the purposes of the [National Labor Relations] Act,” which was enacted to “encourage the practice and procedure of collective bargaining.”

What we’re left with is incredibly simple. History is clear that the only way for the NLRB to protect its election process is to cut down on the number of ULPs committed by employers. The only way to accomplish this is to decrease employers’ incentive to commit ULPs. Barring legislative change, the best way for the Labor Board to decrease that incentive is to increase the utility of bargaining orders, which deprive the employer of the union-free environment it unlawfully attempted to preserve. And the Joy Silk doctrine represents a far more effective form of bargaining order in preventing employer ULPs than its replacement.

True, Board-ordered card-checks (following adjudication of ULP litigation, of course) would almost certainly increase in raw numbers under a Joy Silk revival. But such scenarios would pale in comparison to the amount of free and fair elections that would be conducted in a world in which unfair labor practices are sufficiently deterred. And after all, if employers believe they can persuade workers against choosing unionization without resorting to discharges, interrogations, threats, or other forms of unlawful election conduct, then they should have nothing to fear under Joy Silk.