Kroger's Invitation for Strikebreaking Highlights Bad Labor Law Precedent

The UFCW has no recourse under a 35-year-old Supreme Court case. But Biden's NLRB does not have to follow it.

I originally intended to take a break from substantive legal posts for a few entries after my 10 Recommendations post on Sunday, focusing instead on the political machinations of how a Biden Board can even come to be appointed. But sometimes labor stories emerge in the wild which so clearly demonstrate the decisions and doctrines I want to discuss in Labor Law Lite that other topics must be shelved.

We have lived with the Taft-Hartley Act for 73 years. It is no longer controversial that the National Labor Relations Act lists and denounces certain unfair labor practices of both employers and unions, even though the original Wagner Act only included employer infractions. What should have never stopped being controversial, however, is the NLRB’s increased interference in recent decades with internal union affairs.

The NLRA purports to allow nothing of the sort. Section 8(b)(1)(A) assures unions that the Labor Act will “not impair the right of a labor organization to prescribe its own rules with respect to the acquisition or retention of membership therein” even in situations where a union has restrained or coerced bargaining-unit employees from exercising their Section 7 right to refrain from union activities. The thrust of this language is that while the Taft-Hartley amendments clearly forbade unions from using mass picketing or similar tactics to physically bar workers from entering an employer’s facilities during a strike, there was to be no federal oversight into how unions managed their membership policies (barring more specific legislation, such as Landrum-Griffin’s fair election guarantees or Title VII’s anti-discrimination provision). Most importantly, this meant unions were free to discipline their members pursuant to the terms and conditions of their constitutions and bylaws.

Did the Supreme Court adhere to this standard? Even a cursory knowledge of labor law will tell you the answer is no. The Court got off to a good start in 1967 in NLRB v. Allis-Chalmers, which upheld the use of union fines (collectible in state court) for acts such as a member’s strikebreaking so long as the fines were not coercively steep, arbitrary, vague, or contrary to internal procedural guarantees. The Allis-Chalmers majority grounded its decision in the principles of democratic majority rule and the union’s Section 9(a) duty as the employees’ exclusive representative:

The complete satisfaction of all who are represented is hardly to be expected. A wide range of reasonableness must be allowed a statutory bargaining representative in serving the unit it represents, subject always to complete good faith and honesty of purpose in the exercise of its discretion. … The policy [of exclusive representation] therefore extinguishes the individual employee’s power to order his own relations with his employer and creates a power vested in the chosen representative[.]

The decision was seen as a big win for unions—perhaps too big. Liberal law professors such as James Atleson, Charles Craver, and William Gould joined a chorus of voices from the legal academy which echoed a fear that the Supreme Court had provided unions excessive latitude in enforcing solidarity at the expense of individual rights. It appears this campaign was effective. Following Allis-Chalmers, the Court held that a union could not expel a member for filing an unfair labor practice charge against it even though the member had not exhausted the internal remedies mandated by the union’s constitution. It held that unions were prohibited from fining members for strikebreaking that had resigned their membership but nonetheless voted in favor of the strike and to authorize such fines of strikebreakers. And it held that unions could not maintain a clause regulating the post-resignation conduct of former members to forbid them from abandoning any strike called at any time by the membership.

This rightward drift in doctrine still left one major question to be answered in the 1980s: was it lawful for unions to maintain a more tapered internal rule that prevented members from resigning strictly during an active strike or when one had just been voted for? The Reagan Board said no, trumpeting the concept of “voluntary unionism” that purported to animate the national labor policy of Taft-Hartley. In a 1985 case called Pattern Makers v. NLRB, the Supreme Court upheld this interpretation of the NLRA by a 5-4 vote. Unions were thus powerless to police their own ranks at the most crucial time for maintaining solidarity. Even the narrowest of internal rules were to be invalidated in the face of the individual’s paramount right to aid their employer in strikebreaking.

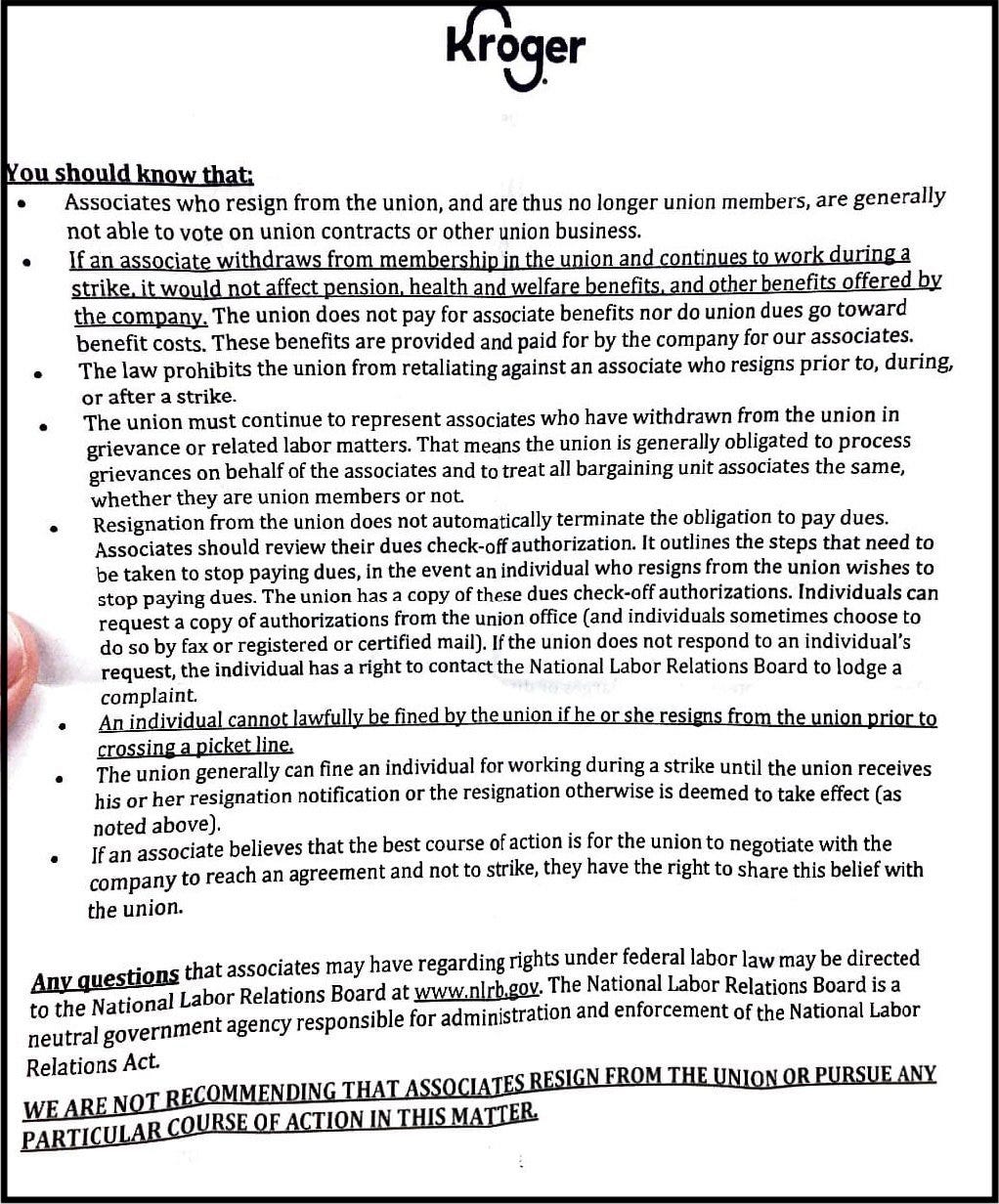

(Pictures posted with permission of Alan Hanson, Mobilization Director for UFCW Local 400.)

This is the state of the law as described in the above letter sent to UFCW Local 400 members by Kroger management after the union rejected the company’s latest contract offer and voted to strike last week: “The law prohibits the union from retaliating against an associate who resigns prior to, during, or after a strike.” Kroger then lists the other legal traps for the union which exacerbate the Pattern Makers rule: its obligation under the duty of fair representation to continue faithfully representing strikebreakers; its duty to speedily process any requests for dues revocations; and its inability to cut off access of strikebreakers to the superior pension, health, and welfare benefits that the union negotiated for them in the first place. A cute disclaimer at the end does nothing to detract from management’s otherwise obvious message.

These facts, coupled with Kroger’s threats to exercise its right to permanently replace any economic strikers, make a compelling case to even the most arduous of union supporters that the right to strike only exists on paper. Worse, the union will only be able to exercise discipline against a strikebreaker that was ignorant enough to fall into the Allis-Chalmers scenario by declining to resign their membership before crossing the picket line.

As will be the recurring theme of Labor Law Lite, I am here to tell you that this case law is not destiny. The Biden Board will not be forced to adhere to the Pattern Makers decision. The majority in that case merely held that the Reagan Board’s construction of the law was “permissible” and thus deferred to the NLRB’s administrative expertise. Justice Byron White, the tie-breaking vote, made this point explicit in his concurring opinion:

Where the statutory language is rationally susceptible to contrary readings, and the search for congressional intent is unenlightening, deference to the Board is not only appropriate but necessary. ... By the same token, however, there is nothing in the legislative history to indicate that the Board’s interpretation is the only acceptable construction of the Act, and the relevant sections are also susceptible to the construction urged by the union. ... Therefore were the Board arguing for that interpretation of the Act, I would accord its view appropriate deference.

In another context, labor law scholar Charles J. Morris has recently argued that the Labor Board may decline to adhere to a Supreme Court decision which emphasizes the permissibility of a past interpretation and instead adopt the other permissible interpretation. The Court should then dutifully uphold this new interpretation as permissible as well.

Of course, I place little faith in the new 6-3 conservative majority to properly apply a more pro-union holding to the NLRA. But I do not think unions have anything to lose here. The alternative is simply to continue adhering to the Pattern Makers decision which works to tighten labor’s legal straitjacket.

These are the sort of fights I urge the Biden Board to take in the coming years. 35 years of living with Pattern Makers has shown us that employers do not need any further help in busting strikes, and it is hardly unreasonable for unions to ask that members file their resignations at any time other than during an active or imminent strike.

The strikebreakers who filed unfair labor practice charges in the Pattern Makers case had participated in the union’s strike vote and simply disliked the democratically-reached result. These members should not get a second bite at the apple by being allowed to resign without consequence. Such an outcome flies in the face of the most basic foundations of industrial democracy, and the Biden Board should get out of the business of regulating this sort of internal union conduct altogether.