The Best Book I Read in 2020

A former NLRB lawyer and New Deal superstar recounts his time enforcing the Wagner Act.

A constant thread in my two-plus years as a practicing attorney has been the pursuit of books, articles, and autobiographies written by lawyers who had more exciting careers than me. I think even those practitioners who sought out this profession solely to make a lot of money thought being an attorney would be more interesting than the average white-collar desk job, but the first few years after law school can really test that theory. And with the labor movement mostly neutered and administrative agencies in an endless state of either timidity or sabotage, young attorneys who want to “do good” in balancing economic power, with the exception of a few elite jobs, must often resort to escapism.

I found Thomas I. Emerson’s Young Lawyer For The New Deal for a few bucks online to read during the early days of the pandemic. It is a memoir published posthumously by the author’s daughter after finding the transcript among his belongings. In short, Emerson was one of the young “hotshot” lawyers in the New Deal administrative agencies who was recruited by a member of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vaunted Brain Trust. Emerson had an unmatched law school resume: he graduated first in his class from Yale; he was the Editor-in-Chief of the Yale Law Journal; and he had spent a semester as a research assistant for future Supreme Court Justice (and then-YLS Professor) William O. Douglas. He could have done anything he wanted to in law, but he turned down offers from a half-dozen proto-BigLaw firms in New York to work as the lone associate in Walter Pollak’s small civil liberties-focused shop. Emerson worked on some fascinating cases for Pollak, including the Scottsboro Boys appeals, but after FDR won the presidency he yearned to be a part of the New Deal. Pollak referred Emerson to another future SCOTUS Justice, Harvard Law Professor Felix Frankfurter, who linked him with FDR advisor Tom Corcoran, who sent him to the new Solicitor for the Department of Labor, Charles Wyzanski. Wyzanski offered Emerson first choice among staff attorney jobs at any administrative agency he wanted, and Emerson quickly picked the newly christened National Recovery Administration because it seemed to be where the most action was in 1933.

Emerson describes being thrown into an exhilarating but tumultuous time in Washington. He and fellow New Deal-ers, flooding in from all over the country, found last-minute housing together while immediately working on high-level cases. (Some of Emerson’s many roommates included Leon Keyserling, the main drafter of the National Labor Relations Act as Senator Robert Wagner’s chief legislative assistant; future SCOTUS Justice and then-Agriculture Adjustment Administration attorney Abe Fortas; and a law clerk to Justice Cardozo.) The NRA’s infamous economic codes were slapped together by attorneys like Emerson pulling 18-hour days. Lawyers shot up the civil servant ladder and earned rapid pay increases, to the point where Emerson believed he was making more than any of his classmates toiling in private practice. Lawyers were constantly being loaned out to newly sprouting agencies on a start-up basis, which is how Emerson came to the National Labor Relations Board in 1934 (the “Old” NLRB, which was founded pre-Wagner Act separate from the NRA). It was there where Emerson found his permanent home when, while “on loan” from the NRA, the latter agency was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. It would also be Emerson’s true love in law.

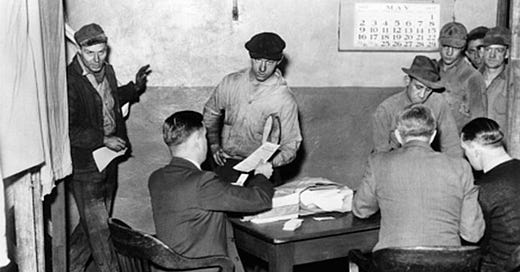

Emerson was one of the many staff attorneys with the NLRB essentially tasked with working from a clean slate of federal labor law. There was barely anything for them to go off, as the NRA’s Section 7(a) was famously vague in the powers it granted to unions. Emerson was immediately tasked with drafting the Houde decision, which first defined an employer’s duty to bargain as one requiring good faith negotiation to reach an agreement. (This was not at all a settled question pre-Section 8(5) of the Wagner Act; many believed the duty only required employers to listen—but not offer counter-proposals—to union negotiators.) Emerson also defended the NLRB’s essential functions in the district and appellate courts, as the agency was flooded with stalling injunction requests from employers meant to test its very existence, and he spent months as emergency counsel for the mediation board commissioned by Roosevelt to settle the 1934 textile strike that roiled the South.

After the “new” NLRB was created statutorily from the Wagner Act to replace the executive order version (rendered powerless by the Schechter case), Emerson was shipped off to the new regional office in Atlanta to serve among the inaugural class of Regional Attorneys. He was tasked with the pivotal job of sifting through the massive influx of Unfair Labor Practice charges for one of the test cases that would serve as an inevitable review of the NLRB’s constitutionality. Few in Washington believed the agency would survive post-Schechter and Carter Coal, but nevertheless the NLRB’s regional and headquarters staff worked feverishly to find and groom the cases that best demonstrated the inherently interstate nature of labor disputes.

This is where Emerson’s career went from interesting to fascinating. He recounts visits to remote company towns in the dead of night to procure frightened workers’ testimony, often resulting in his forcible banishment by police. Emerson trekked the South from factories to mills to farms in search of the evidence he needed for unfair labor practice investigations or initiation of the NLRB’s election machinery. Hearings and trials were held in front of hostile courtroom crowds. As one of the trial examiners stated in his opening admonishment to the audience:

I want to call the attention of the audience to the fact that we’re meeting in the federal court room. The janitor of the building has asked me to please call to your attention that it’s prohibited to spit on the walls. Please refrain from doing so.

In 1936, Emerson was recalled from Atlanta to briefly lead a legal department in the new Social Security Administration. After completing a one-year loan, he happily returned to the NLRB, now as an Associate General Counsel in Washington. The agency had shockingly been ruled constitutional in the Jones & Laughlin case and was now flexing its muscle. Unionization spread like wildfire in the first few years of the agency’s existence, and its record in appeals to the Supreme Court was remarkable. The NLRB aided the La Follette Committee in exposing evidence of what can only be described as industrial terrorism in the way corporations deployed their private police forces and stockpiles of weapons against strikers. In one extraordinary instance, Emerson helped oversee the raiding of wastebuckets from several corporate offenders that had shredded evidence of their unlawful activities. The NLRB’s clerical staff spent countless hours rummaging through the scraps to piece together the damning pages, which were then submitted into the congressional record. By 1939, the NLRB had quickly become the crown jewel of Roosevelt’s administrative agencies.

But as Emerson relays, perhaps the agency was too successful. The NLRB eventually drew the ire of political conservatives and was subjected to an endless congressional probe known as the Smith Committee, named after its segregationist chairman Howard W. Smith. With little backing from Roosevelt, who by all accounts never came around to understanding the importance of a militant labor movement for the durability of his coalition, the NLRB served as a scapegoat for conservatives’ frustration with the New Deal and its dramatic overhauling of the previous legal and economic order. Dozens of NLRB employees were red-baited, including Emerson. (Emerson denied all charges that he was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party.)

While the Smith Committee was not successful in passing legislative reforms to the NLRA, it convinced Roosevelt to replace some of the more radical personnel in NLRB leadership, who in turn weeded out many suspected Communist sympathizers in agency management and the rank-and-file. Emerson was never tarred with too thick a brush, but the self-imposed neutering of the Board that followed this purge convinced him to jump ship in 1940 for new war-time agencies. He worked in the Office of Price Administration before serving as General Counsel of the Offices of Economic Stabilization and War Mobilization, respectively. Emerson’s hectic years in the trenches of the NRA and NLRB prepared him well to lead these agencies, and he eventually traded in this experience for a tenured professorship at Yale Law School, his alma mater. He taught there for more than three decades while litigating many pivotal First Amendment and civil liberties cases, including successfully arguing Griswold v. Connecticut before the Supreme Court.

Despite living a satisfying life as an Ivy League professor and impact litigator, it is apparent from Emerson’s memoirs that he disdained the NLRB’s moderate shift and regretted not being able to make a career there. I’ll reprint his words in full, as they describe a veritable utopia for young progressive lawyers:

I never enjoyed any period of my career more than my five years with the NLRB. I felt a sense of mission, a sense of active struggle against opposition, and a sense of accomplishment. I believed that the work the Board was doing was extremely important. I had believed from the very beginning that the National Labor Relations Act was the key piece of legislation in the New Deal. By establishing the power of labor to organize into associations, the act was creating an institutional force that would support the liberal measures that the New Deal advocated. This would be the most significant organized force in support of the New Deal and in support of the chance in the social, political, and economic structure of the country—which I thought was necessary.

I also believed that the job was performed more in accordance with the principles of sound government and more efficiently than had been true in the NRA, for instance. Here we had time to assess the situation and gradually work out procedures that were reasonably well-balanced between the government’s interest in efficient operation of the law and the individual’s interest in a fair chance to present his viewpoint and be treated fairly. I believe the Board was doing a fine job. Despite opinions that the Board’s position was too intransigent, I am convinced that the Board’s interpretations of the Act and the Board’s aggressive enforcement of the Act was what was needed. I was not willing to make any substantial concessions to the practical politics of the situation.

I sensed more unity at [the] NLRB than in any other organization in my experience, before or since. The harmony that existed among the various factions at the NLRB is rare. There were differences of opinion, but the staff had sufficient goodwill toward each other and sufficient devotion to the ultimate objectives that concessions were made willingly. We negotiated decisions that were satisfactory to everyone. The result was a tremendous esprit de corps. I attribute a good deal of it to the leadership of Chairman [Warren J.] Madden. His integrity generated such respect, his ability to compromise and his perspicacity about people and their viewpoints promoted such resourcefulness that he towered above the situation and was largely responsible for the remarkable harmony. . . .

The NLRB of my time became a legend among government lawyers. As young lawyers arrived in Washington, they would hear tales of an agency that was characterized by tremendous courage, great ability to resist pressure, and great tenacity for its positions. Some look back with longing at the way the Board backed up its subordinates who basically were performing well, but who got into some immediate difficulty. Even now [1953] it is regarded as an unusual government agency, with which young idealists could be happily associated, but alas, it no longer exists in that form.

That is, to a tee, everything I want out of a career in labor law. The legal left should strive to cultivate these sort of work environments and push for regulatory movements that inspire the same sense of dedication and justice among its staff. We would all be much better for it.

As a young soon-to-be labor attorney, Emerson’s account of being an early NLRB attorney gave me goosebumps. I personally loved my time at the NLRB, and I definitely felt the sense that these attorneys cared about workers' rights. Plus, who wouldn't love a cozy fed job with that juicy pay-grade?

Thanks for recommending this -- will have to track it down.

Have you read "The Forgotten Memoir of John Knox: A Year in the Life of a Supreme Court Clerk in FDR's Washington?" A fascinating account of a nightmarish year working for anti-New Deal fanatic James McReynolds.