Why We Need More Labor Lawyers On The Bench

Few federal judges have any background in labor law. Workers suffer from this dearth of knowledge.

Very few federal judges have experience as former labor lawyers. Many scholars and activists have written about this phenomenon, and I’ve discussed it with regards to Obama’s judicial picks and Biden’s agenda. This dearth of workplace legal knowledge, especially from the union side, almost certainly has deleterious effects on workers’ rights; one prominent professor has gone so far as to suggest it’s an indirect example of class war.

Biden hasn’t nominated many federal judges yet, but we’re already seeing a disappointing trend carry over from the Obama administration. In what is likely an outsourced pick from Senators Cory Booker or Robert Menendez, Biden nominated Christine O’Hearn to the District of New Jersey, who, among other things, “represents employers in union related matters including matters before the National Labor Relations Board such as petitions for certification, elections, and unfair labor practices as well as collective bargaining negotiations, grievances and arbitrations.”

As I discussed in my earlier post, Obama nominated more management-side attorneys like O’Hearn than he did union-side attorneys. Biden has so far done the same.

Any labor lawyer with experience practicing in federal court can tell you that it is extremely difficult to convey complex labor law issues to most judges. Labor law is an incredibly niche area of law that has little spillover into other subjects, creating a specialization issue where only a few lawyers ever gain expertise in this field. So most judges have no memorable experience in the doctrines presented, and, perhaps more importantly, the decline of labor law as a subject of prominence in law school means the judges’ clerks are completely ignorant of the issues. This chasm in knowledge between the parties and the courts has the potential to get worse every year so long as union density continues to decline, which shrinks the demand for labor lawyers.

But so long as union organizing continues, and the National Labor Relations Board exists to referee these campaigns, the legal issues which arise remain of pivotal importance to workers. And few stakes are higher in labor law than those surrounding the NLRB’s pursuit of so-called “10(j)” injunctions.

Section 10(j) of the National Labor Relations Act authorizes the NLRB to seek temporary injunctions against employers and unions in federal district courts to stop unfair labor practices while the case is being litigated at the trial stage before an administrative law judge. These injunctions are typically sought in “nip-in-the-bud” cases, wherein a vocal union proponent is discharged to intimidate fellow workers from supporting the union, but 10(j) can be applied to a vast swath of circumstances: unlawful subcontracting of bargaining-unit work without negotiating; unlawful withdrawals of recognitions from unions; refusals-to-bargain by a successor employer; and picket-line violence or striker misconduct.

Despite 10(j)’s broad potential, it has historically been underutilized. The General Counsel’s office made efforts in the 1970s to begin seeking more injunctions for the rising number of unfair labor practices filed by unions, but the Reagan Board under the leadership of Chairman Donald Dotson sabotaged most attempts to apply it to employers. Democratic appointees under the Clinton and Obama administrations attempted to institutionalize injunctions in the context of nip-in-the-bud cases, and it was even applied in the high-profile context of the 1994-95 Major League Baseball strike. But 10(j) injunctions remain only a small part of the NLRB’s repertoire.

Part of the reason why 10(j) isn’t a slam-dunk remedy for workers and Labor Board prosecutors is that the delays inherent in the administrative and judicial processes frequently defeat the very purpose of the injunction. But what if you draw a judge who knows exactly why speed is so important in this arena?

We can see a glimpse of how the system should work in a 2019 case out of the Middle District of Pennsylvania, NLRB v. Mountain View Care and Rehabilitation Center. The facts of the case are routine. Yolando Ramos was an employee at a nursing facility. Ramos vocally supported a union drive of service and maintenance workers at the facility. She was the only employee in the department collecting signatures for a service and maintenance unit. The employer fired her on March 5, 2019, shortly after she began collecting the signatures. The organizing campaign promptly stalled out.

The Union filed an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB’s Philadelphia regional office in late March, alleging classic violations of Sections 8(a)(1) and 8(a)(3) of the NLRA. The Region found merit to the charges in its investigation and issued a complaint against the employer on May 16, 2019 while setting a trial for July. But a win at trial wouldn’t be worth much for Ramos or the Union if reinstatement came years later after the appeals process took its course; the employer could challenge an ALJ’s reinstatement order at the Board, a circuit court, and even the Supreme Court. By then, Ramos would be at a different job and the union drive at the affected unit could be long gone. So the General Counsel’s office sought and obtained authorization from the Board for a 10(j) injunction over the course of the following weeks, and on June 24, the Region filed its petition in federal district court, seeking reinstatement of Ramos pending the outcomes of the July trial (and any subsequent appeals).

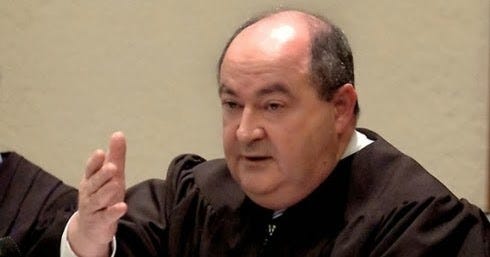

The case was assigned to Judge Robert Mariani. Mariani was one of the few labor lawyers nominated by Obama to the federal bench, having represented unions and their members for decades in the state of Pennsylvania. His long career of service for organized labor left him well versed in the need for quick remedies in campaign-related violations, so it’s not surprising that Mariani gave the injunction request red-carpet treatment on his docket. The Judge scheduled an expedited hearing on the injunction for July 1, 2019—a mere five court days after the petition was filed—and issued a memorandum opinion finding in favor of the NLRB’s request one day after the hearing was held.

The opinion is short and sweet. Mariani found that the NLRB’s attorneys had made their case that there was a reasonable likelihood of victory at the ALJ trial and that injunctive relief was “just and proper” in the interim. Judicial scrutiny of such petitions are (supposed to be) very narrow, and Mariani got out of the Board’s way as required with only minimal probing.

The employer proceeded to settle the case after the ALJ decision. Justice was restored for Ramos, and more importantly, the Union eventually won its election and secured a first contract. This was the system working as well as it possibly can in its current statutory form. It still took four months from the point of discharge to court-ordered reinstatement, but that’s not so long that the firing wasn’t fresh in workers’ minds. Restorative remedies for a fired employee can clearly revive a dormant organizing campaign.

This is how the NLRA can and should work with the right effort from the General Counsel’s office and proper deference from the judiciary. President Biden has already nominated the right person for the GC role in Jennifer Abruzzo, but he has a long way to go in putting labor-minded jurists on the bench. As the Mountain View Care and Rehabilitation Center case demonstrates, Biden should prioritize more judges like Mariani in future nominations.

What is needed is a specialized Federal District Court of Labor Law.

Great piece!